The Initiation

Meandering around sparrows, koels and orioles, I find meaning and life purpose in nature. This is the story of my initiation into birds.

My first job was all desk work for eight hours a day, in an air-conditioned, modern corporate office — the type that’s glass on all sides, to bring the outside view right into your workspace, to make you ignore how boxed in you are. It’s how I felt on most days sitting at my desk with ringing phones and glaring computer screens all around, the oppressiveness of it made bearable by the natural wallpaper on the glass walls anywhere I turned. I’m grateful for the glass walls many times over; if not for it, I wouldn’t have spotted my first Golden Oriole.

Golden Oriole

The blinds next to the coffee vending machine were up, so my eyes strayed out to the nearest tree. The dark green leaves of the mango tree didn’t even flinch. It was a quiet afternoon both inside the office and outside. Almost immediately, I spotted a bright yellow patch in the foliage. I had to take a second look because this wasn’t mango season; it was impossible that a lone mango could dangle in the tree at this time of the year. It turned out to be a bird. A bright yellow, myna-sized bird with a pink beak and a black eyepatch. I thought I’d struck gold! It flew out a few seconds later, and I rushed back to my desk to find out what exactly I had seen. Googling the bird’s features gave me the name in a few seconds. Golden Oriole. I read all I could about the bird for the next few minutes with a mixture of excitement and disappointment - excited that a pretty bird like that inhabited urban spaces, disappointed that I would not make news headlines. A few months later, I bought a proper bird guide and a pair of binoculars, signed up to online nature forums and made birdwatching trips outside the city every weekend.

I remember this incident because it was a turning point in my journey as an active nature photographer. But it wasn’t the first time that observing birds had excited me. It went way back.

* * *

When I was seven years old, we had to move out of the flat we were staying in. Amma found an old house for rent. It was built in the '60s as part of a housing society for government employees. It looked as rustic as a cottage on the edge of the woods, even though it was a townhouse in a busy neighbourhood. The landlady had lived in it till her husband’s death and had now moved to a different part of the town with her grown sons. She couldn’t be bothered about the upkeep of the place. It was messy and looked older than it was. Every other house in the neighbourhood that shared the same history had had a makeover to upgrade its appearance and its amenities. Not this one. The old lady, however, wanted the same rent the others in the area were fetching. It was slightly more than Amma could afford and much less convenient than she would have liked, so she wasn’t sure about it. But she decided to take it when she looked at my face the first time I saw the house - it had a large backyard with a mango tree that looked as old as the house and an equally large front yard with a large Parijata tree and a rundown garden that looked so wild that I was transported to a different world. All a child needs is a few trees and enough space to make up her own wonderland.

We lived there till I reached high school. It’s where I learned that trees are more than just an ornament or a vending machine. Trees, to my surprise, were mini cities for all kinds of creatures. Summers were a busy time for the mango tree and the koels never let me forget it. I’d tease the koel by imitating its call; it drove the poor bird nuts! Every time I called out, he called back louder. It would go on and on. Each time I mocked him, his reply got louder and angrier, until I grew bored with the game. He was never the first one to blink. Amma told me it was cruel to mock him but it was rib-tickling to me. She said the call I heard often and imitated was from the he-koel. He liked to have his tree to himself and his she-koel, with no trespassers. My imitation calls were causing him distress because he thought it was a rude intruder of his own kind and he couldn’t find the trespasser to shoo him away. How did she know it was a he-koel? She said the she-koel had a different song, a faster paced one. She looked different too - bigger than the male with white bars all over her body. Eye-catching yet almost impossible to find in the thick foliage. I spent many hours of the summer vacation under that tree with my neck craned up to spot the pair and observe their antics. I’d try to resist the temptation to tease the male bird but my callous side sometimes got the better of me.

House Sparrow (female)

Avian summer festivities didn’t restrict themselves to the garden alone. One morning, Amma woke me up early with an excited voice, “What do you know, the sparrows are building a nest in the living room!” I suspected this was a ruse to get me out of bed early, something most children refuse to do on holidays. Miffed yet curious, I went into the living room and found nothing out of the ordinary. Amma grinned and pointed to the ceiling fan. A sparrow perched on a blade, facing the ventilation window just below the ceiling. Another sparrow sat on the window gap with a few strands of hay in its beak.

Those days, it was unthinkable to keep doors of the house shut. The front and the back doors were open from the time the first person woke up till sundown when lamps were lit. Sparrows or any creature could come in and out of the house as they pleased, as long as they didn’t fear us and we were certain they weren’t venomous.

Years later, when I read E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India, I chuckled at the author’s observation of creatures in India: “… no Indian animal has any sense of an interior. Bats, rats, birds, insects will as soon nest inside a house as out; it is to them a normal growth of the eternal jungle, which alternately produces houses trees, houses trees.”

That summer we didn’t turn the ceiling fan on, for fear that the birds might get accidentally hurt. It meant we could only go to the living room during the cooler parts of the day. That gave them enough confidence to settle down in their chosen spot comfortably. Amma didn’t mind cleaning up after them as they dropped hay all over, in their nest-building frenzy. She didn’t complain even once about the mess they made of the living room.

Yet again, she could tell the male and female sparrows apart. “Check for the black patch under the throat”, she pointed out to me. “That’s the he-bird.”

House Sparrow (male)

There was payasa one day for lunch. Amma said that little baby sparrows had peeked out of the nest that morning for the first time, so we had to celebrate. It was just as festive when our cat gave birth to her first litter in an old pot in the storeroom.

* * *

I spent my high school days in a house in the suburbs, on the edge of farms, dividing my free time between reading and exploring the land around. With farms so close, I met new birds that even Amma didn’t know names of. So we made up fun names of our own. The Indian Robin flicking its tail shamelessly to show off the red undertail coverts had to be “kempandina hakki” (the bird with a red butt), the bulbul came to be “chotte hakki” (crested bird) and so on. To my delight, my school library ordered new editions of K. P. Poornachandra Tejaswi’s books and story collections - many of them on birds and his life in a coffee estate in Mudigere with his dog Kiwi. Through his books we learnt the Kannada names of our bird visitors, but most days we preferred our made-up names.

The cover of ‘Malenadina Chitragalu’ by KuVemPu featuring the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo

One bold bird Amma knew well and was very fond of - with its glossy black plumage and a forked tail it sallied back and forth from electric cables and street lamps. It was a “Kajana” (Drongo), Amma noted, KuVemPu’s favourite bird. Known as Rashtrakavi, KuVemPu (pen-name for K. V. Puttappa) is a household name in Karnataka. His writings feature nature and the forests around his hometown nestled in the evergreen Western Ghats. His love for the the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo (a cousin of the more common Black Drongo), only found in the deep jungles of Western Ghats and the Himalayas, is legendary. The flamboyant bird with its long tail feathers features regularly in his writings and even on the covers of almost all his books. When he started his own publishing house, Udayaravi Prakashana, the logo was an illustration of two drongos swirling around each other. (K.P. Poornachandra Tejaswi, from whose writings I learnt so much about nature, was KuVemPu’s son. No coincidence.) That’s why Amma was fond of the bird - it reminded her of KuVemPu’s writing and as a result, of her own ancestral home in the Western Ghats.

Google Doodle on Dec 29, 2017

(Google honoured KuVemPu and his love for drongos with this Google Doodle on Dec 29, 2017 for his 113th birthday.)

* * *

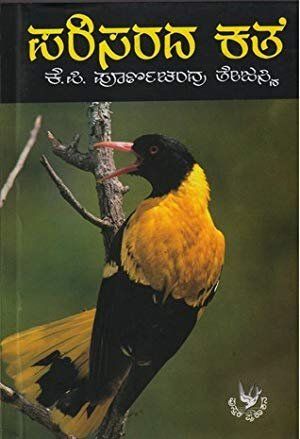

Black-hooded Oriole on the cover of ‘Parisarada Kathe’ by K.P. Poornachandra Tejaswi

Things didn’t remain as idyllic once the pressure of college education started to mount. Eventually, the need to earn a living pushed me to the big city. To cut to the chase, the days of my birdwatching faded away from my life and my memories. I found myself in a glass box, amidst constantly ringing phones and glaring computer screens. Waiting for kingfishers on the edge of open wells in neighbouring farms was like a story from another world. Until the Golden Oriole. I now believe that the Oriole came as a messenger from my ancestors who lived their entire lives in the tropical rainforests of the Western Ghats, conversing with birds and beasts more often than humans. (Incidentally, one of my favourite books by Tejaswi that I loved as a child ‘Parisarada Kathe’ (Nature’s story) features a Black-hooded Oriole on its cover. Message received, loud and clear.

Since then, I have asked myself many times why I watch birds. I ask my birdwatching friends this question. All of us list out as many reasons as we can, explaining how fascinating birds are. The more eloquently we talk about them, the more we show how much we have learnt about them. But what drives us in the first place?

A friend asked me the same question last week: why do you watch birds? The way he emphasised on the ‘you’ made me think hard… perhaps it was the koels and the sparrows. Or was it the mango tree and the wild garden? Or something that came before that…

* * *

Scaly breasted Munia

In the middle of the monsoon season this year, Amma came to me with an excited voice. “There are birds nesting in my bathroom window!” I went to her room and peeked in carefully. In the gap between the wired mesh and the window grill, two scaly breasted munias had sneaked in fresh strands of grass - a whole clump of it and awkwardly stuffed it into a ball-shaped nest. Her presence in the bathroom didn’t spook them. They seemed to have figured out that they can’t be reached from the inside. I worried, however, that this nest wasn’t a great idea. Going in and out of the gap was a clumsy job, the position of the nest didn’t seem at all comfortable, but hey, I wasn’t being called to judge. The female munia apparently judged it to be the best.

In the course of the next few days, Amma gave me updates on the progress. Apparently, the male had given up several times (ha! I knew it!) but had to resume building because the female would sit on the window for hours without moving an inch, insistent that the nest be at that exact spot. Every time, the male bird gave up, Amma was disappointed. When he picked it back up, she cheered up. Until one day, after Deepavali, the birds gave it up for good and didn’t return. Amma was visibly upset. I told her that munias make several attempts at nest-building before finally making an inhabitable one and this was par for the course. All that hard work for nothing, she lamented. I tried to explain that this is common among munias. In fact, the younger the birds, the more the number of failed attempts. Way of the world. These days, I often become conscious of how our roles have reversed.

A few days later, I was at my desk in the study room right below Amma’s room. I looked up from my screen when a blip flew past. It was the munia with a blade of grass, trying to build a nest in the neighbouring house. Should I let her know the munias weren’t gone? She’d be setting herself up for another disappointment. It was mid-November. The pair should have been raising young ones by now. This bird was clearly in his first season. Maybe his luck (and skill) will improve next monsoon. I told Amma anyway. Like I had guessed, her eyes instantly lit up with hope. That was good enough for now. If a little bird offers a bright new outlook for the day, why not take it? Isn’t that one of the gazillion reasons we watch birds?

* * * * *